Direct Benefit Transfers: A revolution under the radar

By Sriram Balasubramanian

In the run up to the 10th anniversary of the Narendra Modi government, there have been numerous comparisons between the performance of the government viz-a-viz previous regimes. The release of the NSSO survey results for 2022-23 and its projected elimination in extreme poverty has further enriched the discussion. While there have been numerous comparisons especially on macro-economic parameters and the poverty indicators, one thing that stands out is the efficiency of welfare schemes which has been significantly better in recent times. At the core of this increase in efficiency is the development of the Direct Benefit transfer system and its scalability in recent times.

The DBT has been well talked about by many researchers over the years. The IMF’s book on inclusive growth consists of a chapter on inclusive growth in India and highlights the DBT system in detail. In very simple terms, it optimizes the JAM trinity—Jan Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile---to ensure that cash transfers are transferred directly to the bank account of beneficiaries. For the year FY 2023-24, approximately Rs 5,45,599 crore has been transferred to almost 668 crore beneficiaries through 315 schemes and 54 ministries. Cumulative DBT transfers for all the years since its inception is a whopping Rs 35,30,011 crore. One wonders what has made the DBT such an important part of the developmental narrative and why its central perhaps to future progress as well. There are three main reasons.

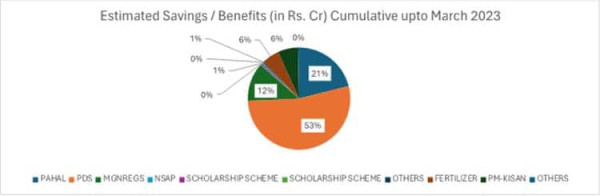

First, besides the technology, the recent scalability of DBT across many states in India has ensured that corruption through middlemen (on welfare schemes) is significantly reduced. Leakages of the system for direct cash transfers has been reduced significantly since the money reaches the beneficiaries directly into their bank accounts. This has generated significant monetary savings which we define in economics called the ‘opportunity cost’---what would have been the cost had the DBT not been there? The answer to this question is staggering. According to the chart shown below, the cumulative savings in the DBT schemes from has been a staggering Rs 3,48,564.66 (approx. Rs 3.5 trillion) crores from the beginning of the DBT around FY2015 to March 2023.

Source: DBT website

Source: DBT website

This Rs 3.5 trillion is spread across the main flagship schemes such as PDS, MGNREGS, PM-Kisan and PAHAL schemes among others. Most of the efforts have been to cumulatively eliminate fake ID cards and beneficiaries and ensure that people receive the benefits of these schemes. If these numbers are legitimate, no reason to suspect otherwise given that its official data, then the opportunity cost of not having a DBT is huge. This could exceed the budget of various other big-ticket investments and schemes that have been conceptualized. For example, the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan’s allocated budget from 2014-15 to 2021-22 is Rs 83,970 crores and funds released to states is about Rs 74,411.8 crores. In fact, when compared with the cumulative general government net lending/borrowing from 2015-2022 as per IMF WEO data, the amount of savings is almost 2.5 percent of the net general government net lending/borrowing figure! Such is the enormity of the savings that has been accrued as shown by the data for DBT thus far.

Second, besides the savings which has been accrued by reducing corruption, there seems to have been an inherent ability to transfer these direct transfers to beneficiaries into consumption driven benefits. Given the vast UPI ecosystem which has been developed, the transfer rate from the benefits accrued to consumption levels at the lower percentile levels seems intuitively significant. A direct comparison of the lower fractile levels in both the NSSO 2022-2023 and NSSO 2011-2022 data without the micro-data available for the former would be an incomplete assessment.

However, the generally overarching trend from the summarized NSSO2022-2023 analysis is the consumption at the lower end of the fractile distribution has improved significantly at the lower fractile levels in the latest surveys. One of the possible reasons could be the greater efficiency in welfare transfers and as an extension, because of the UPI digital stack’s popularity across India, its possible conversion from some of these savings from these transfers to consumption per se due to greater transmission triggered by the UPI digital stack system. The increase in consumption options for people across the spectrum due to technology access has further enhanced this transmission more in recent times. Furthermore, this end-end digital process (from source of income/transfer to point of consumption via bank accounts) has also ensured that there is massive empowerment at the ground level.

This brings us to the third transformation. At the ground level, the expansion of DBT and the integration with UPI, has ensured that women (especially rural women) are empowered significantly. For example, in the erstwhile system, much of the PDS benefits would be siphoned off from rural women by drunkard men for their purposes. Due to the evolution of the DBT, not only are the women empowered by having the benefits in the bank account, it also seems to have ensured that they spend independently and wisely reflecting higher consumption standards at the lower decile levels as well. This liberates them and allows them to make sensible and prudent consumption choices unlike before. Equally importantly, this also empowers the poor (irrespective of gender) at various levels. It provides the poor a greater variety of choices and a wider price point for many products which they have access to unlike before. Besides providing them a bank account and financial access, it also ensures that the poor are far more well informed than before in making wise consumer choices.

In retrospect, the entire DBT ecosystem needs to be far more appreciated than what it is given for. For the real poor and the disenfranchised, its transformational at various levels and is the fulcrum of welfarism in the modern Bharat. The ‘opportunity cost’ of DBT is high given the level of savings that it has accrued, its possible integration with UPI and its possible impact on consumption levels and its ability to empower women and the poor has been unprecedented to say the least.

Sriram Balasubramanian is a renowned economist and best-selling author of Kautilyanomics for modern times. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.