Food costs are falling, as farmers help slay the inflation dragon

The headlines suggest catastrophe for the global food supply: Biblical heatwaves, floods, storms and wildfires. And yet, in the world’s breadbaskets, the weather has been fair this growing season — so good that we’re facing an oversupply of key agricultural commodities and thus much lower prices than in 2022 and 2023.

If the favorable weather persists for a couple more months, the low farm prices we enjoyed from 2015 to 2020 are on the cusp of a return. In a world still unconvinced that inflation has been slain, the drop in wholesale food prices

means there’s one less thing for central bankers to worry about as they ease monetary policy.

Let me emphasize the word “wholesale” — what you and I pay depends upon numerous other costs — and on whether manufacturers and retailers pass on the savings or expand their profit margins.

The fine weather stretches from the US Midwest to the plains of Kazakhstan; from the Brazilian savannah to the Australian grasslands. Even in my home country of Spain, so important for olive-oil production, the growing season has been about right.

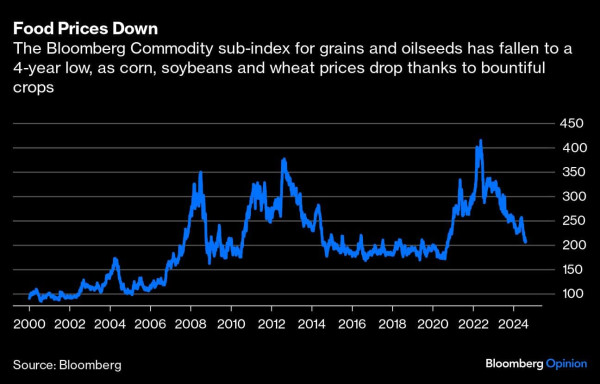

The market is frontrunning the expected bumper harvests. The cost of wheat, corn and soybeans has already fallen to a four-year low, down about 50% from the all-time high set in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Rice prices are lagging, but those costs are about to hit a one-year low. Olive-oil prices, closely tracked in my kitchen, are down 25% from their record high set in January, and probably have further to fall.

Of course, there are exceptions: Coffee prices remain sky high, while the costs of cocoa and some vegetables remain high by historical standards. At supermarkets and restaurants, prices are also higher than before, but that has a lot to do with energy costs and wages, rather than food inputs.

To be sure, it’s hot – too hot: July marked the 14th-consecutive month of record-high temperatures for the planet, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But that doesn’t mean catastrophe for the world’s breadbaskets.

The weather isn’t the only reason why the world is heading toward lower food prices. The last two decades have seen huge improvements in agronomics. Seeds yield far more than before, even when rain and temperatures aren’t ideal, and irrigation has expanded. Farmers have access to much better hardware: large planters, powerful tractors, improved combines, larger storage facilities.

Compared with a decade ago, the world will harvest in 2024-25 about 10% more wheat, about 15% more corn, nearly 30% more soybeans, and about 10% more rice. Except for corn, all the other three key food commodities will enjoy a record high production.

Few regions show that combination of fair weather and scientific advances more clearly than the American Midwest.

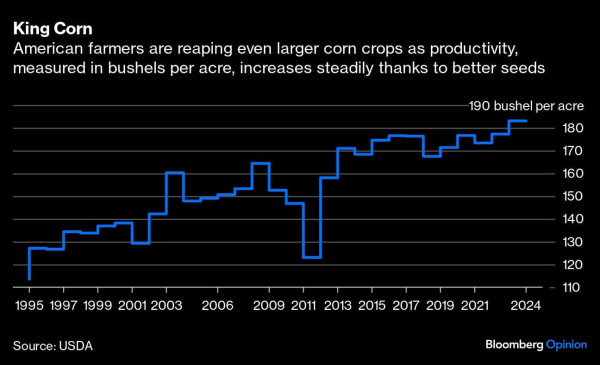

On Monday, the US Department of Agriculture said it anticipates American farmers will reap record yields for two key food commodities: on average, 183.1 bushels per acre of corn, and 53.2 bushels per acre of soybeans. Those numbers may sound alien to anyone who hasn’t set foot on a farm. Scott Irwin, a veteran agricultural economist at the University of Illinois in Champaign, about two hours drive south of Chicago, put the statistics into a very graphic description of the overgrowth: “jungle-like.”

It’s not an exaggeration. Two decades ago, US corn farmers were harvesting about 150 bushels per acre; in the mid-1980s, the number was closer to 110 bushels. To harvest anything north of 180 bushels is astonishing. That’s the kind of numbers one would have expected in irrigated conditions only, where farmers don’t rely on the whims of the weather.

Put another way, this generation is harvesting about 90% more soybeans per acre than its parents did 50 years ago; and about 110% more corn. All of that improvement is due to agronomics: seeds, pesticides, fertilizers and machinery. The weather hasn’t played any role there. If anything, perhaps, the US Midwest is benefiting from warmer temperatures.

Unsurprisingly, commodity traders and farmers alike are pricing it in: Corn is trading just below $4 a bushel, typically a level that signals a well-supplied market. Soybeans are below $10 a bushel, again a level than indicates more than enough production. Corn and soybean prices filter into the rest of the economy via meat prices, as the drop in feed costs typically increases livestock supply and, ultimately, meat and poultry.

It would be wrong to confuse a few months of fair weather with the long-term threat of climate change. But for now, thanks to better-than-expected rains, temperatures and agronomics, the world is heading to bumper crops and lower crop prices. Enjoy while it lasts.

Credit: Bloomberg