I went to Iceland for a road trip. I left with climate anxiety.

JÖKULSÁRLÓN, Iceland — I feel like I am watching the end of humanity.

As gusts of wind and rain sweep across the glacial lake of Jökulsárlón, milk-white and light blue icebergs slowly drift toward the Atlantic Ocean, circled by otters and birds. Crowds of spectators in rain gear pose for selfies. Others, eager to get a glimpse of the ice formations up close, board an amphibious boat.

A few hundred meters away, chunks of ice have washed up on the shore, standing out like crystals against a backdrop of black volcanic sand. Photographers, shielding their cameras from the swirling sand and rain, rearrange the ice blocks in search of the perfect shot.

“The global surface temperature has increased by circa 1 degree Celsius on average since pre-industrial times and considerably more in the Arctic,” I read on an information sign illustrating how glaciers around the lake have retreated since 1890. Over the last 50 years, the lake near Iceland’s southeastern coast has quadrupled in size.

Just like millions of other tourists, it was my fascination for its otherworldly landscape and natural wonders that attracted me here this August. Yet as the tourism sector booms, it’s precisely that nature that is undergoing irreversible change, forcing the island to rethink how it attracts tourism — and manages its impact.

Iceland expects some 2.3 million tourists this year, nearly all arriving by plane at its only international airport, built by the U.S. military during World War II. That number is only projected to grow in the so-called land of fire and ice, which is home to some of the most active volcanoes on earth — but to fewer than 400,000 human inhabitants.

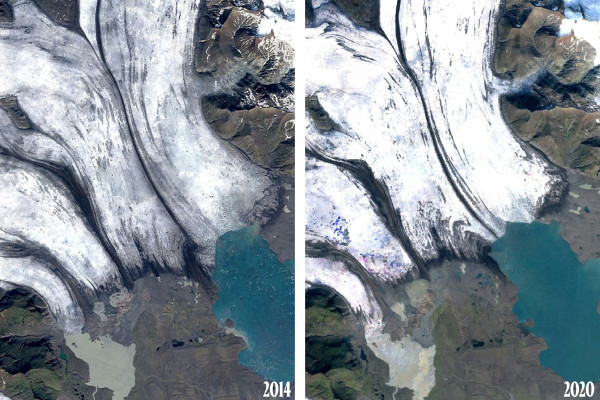

At the same time, glacial melt across the globe is accelerating due to climate change. With ice sheets covering some 11 percent of its surface, the North Atlantic island once entirely covered in ice is particularly affected. Since the beginning of the century, Iceland has lost some 750 square kilometers of glacier — around the size of the Asian city state of Singapore.

“People are coming to visit nature and to experience the unique landscapes and … see that particularly the glacier environment here is affected heavily by climate change. You see it already now,” said Hans Welling, a researcher at the University of Iceland who studies how climate change is affecting Iceland’s tourism industry.

Climate changes

Curiosity about Iceland’s waterfalls, geysers and hot springs had also brought my U.S.-based friend and me to the country. Having bonded over hiking trips to the Highlands during our university days in Scotland, driving the famous Ring Road, exploring lunar-like lava fields and pitching our tent in the midnight sun had been a long-shared dream.

A dream it was — but with an increasingly unsettling undertone.

In the northern town of Húsavik, which almost touches the Arctic circle, we marvel at humpback whales. Only 10 to 20 years ago, the species wasn’t found in local waters, having only migrated due to changes in the ocean food web, I read in my guide book.

As we drive east, my friend keeps pointing out fields of purple-blue flowers that, despite their charm, seem out of place in the rough terrain. With the help of her plant-identification app, we soon find out the Alaskan lupine, first embraced as welcome cover for eroded land, is now considered an invasive species, threatening Iceland’s ecosystems.

After pulling out of the busy car park near Jökulsárlón, having spent minutes staring at the icebergs floating in the lagoon, we fall silent.

Vatnajökull, Europe’s largest ice cap, is melting at record speed. That causes the calving of its offshoot glaciers, such as Breiðamerkurjökull, the one feeding the Jökulsárlón lagoon, to accelerate. In Jökulsárlón, which only started forming some 90 years ago, that effect is sped up further by saltwater from the ocean feeding into the lagoon.

The industry has responded by increasingly switching from popular glacier hikes to boat tours around glacial lagoons — as long as those are still possible.

Only last weekend, at least one person died after an ice cave that a group of tourists was exploring partially collapsed. While simply linking that particular incident to climate change would be a mistake, we “will probably get more of these types of accidents in the future,” said Welling.

Tourism management

The impacts of climate change on tourism in Iceland vary: extreme weather events are expected to become more frequent and severe, with climate change playing a “significant role,” said Welling. But warmer temperatures will also make outdoor activities more pleasant, he added.

And while Iceland profits greatly from its tourism boom — which accounted for 8.5 percent of its GDP in 2023 — it is acutely aware of the sector’s impacts on its increasingly fragile ecosystems.

In a bid to raise funds for sustainability programs and mitigate the environmental impact of mass tourism, the government reinstated a tourism tax at the beginning of the year. New Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson has vowed to crack down on the negative impacts of overtourism, floating a tourism tax collected at specific sites.

“We would like to lean more towards a system where the user pays. As I see it, we would want to go more toward accession fees to the magnets, as we call them, around the country,” he said in June.

Continuing on our way along the Ring Road, I am soon forced to pull over as torrential rain and fogged-up windows make driving increasingly unsafe.

Once we resume our journey, now with a revived need to share our thoughts and impressions, we soon reach another glacier and its lagoon. The rain slows, giving way to a rainbow over patches of misty clouds.