In 8 charts: Govt's interest cost share in GDP beats capex outlay share in FY24; what's driving this surge?

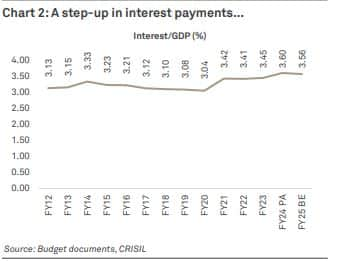

Interest payments have been rising steadily since the pandemic and stands at 3.6 percent of India's gross domestic product (GDP) in FY24, which reduces the fiscal flexibility the government has, according to a Crisil Quickonomics report.

The share of interest payments had been falling till FY20, when it was 3.04 percent, and after that it has been on a steady rise.

This increase reduces the legroom the government has to decide on its spending; to put this in context, as the Crisil report pointed out, share of interest payments in GDP has exceeded the budgetary capex of 3.2 percent in FY24.

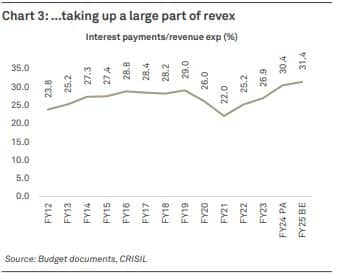

It takes up more than 30 percent of government's revenue expenditure.

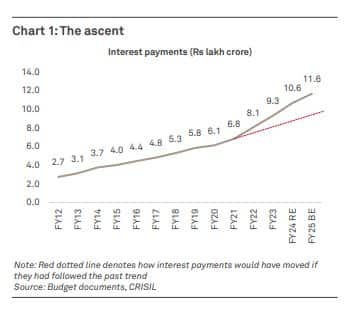

The growth in interest payments accelerated after the pandemic. As the report stated, "After growing at 8.8 percent on an average annually in the five pre-pandemic years (fiscal 2016 to 2020), interest payments surged 14.9 percent, on average, in the past four years (fiscals 2021-2024)".

Also read: Fiscal Deficit: Go easy or pull back? What markets are likely to reward

The analysts said there were various factors behind it.

As the reported stated:

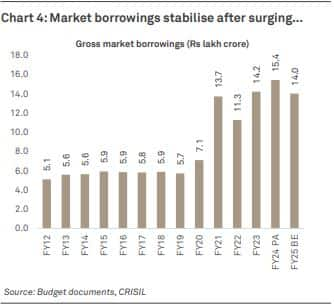

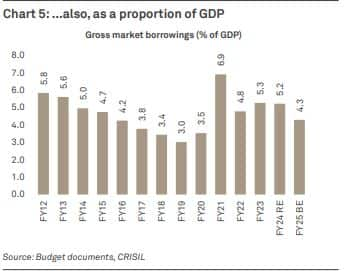

1. Higher market borrowings: Interest payments are a function of how much the government borrows and at what rate of interest. Gross market borrowings have shot up since fiscal 2021.

The report added, "While some reduction in borrowings is budgeted in fiscal 2025, they remain notably above the trend in gross terms and in relation to nominal GDP".

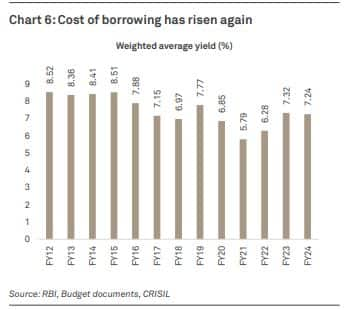

2. Secondly, the cost of borrowing has gone up. As the report stated, "A dominant part of the interest payment in a particular year is a function of the interest rate at which the debt was issued in the past."

The government’s weighted average cost of borrowing was high even before Covid, when it was 7.34 percent on average, in the immediately preceding five years or between FY16-FY20 and it was above 8 percent before that. This "partly accounts for higher interest payments in recent years".

The cost of borrowing fell during the pandemic year and then firmed up in the last two years, noted the analysts.

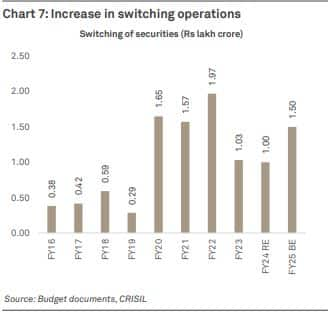

The government has also been "switching" more frequently, which is when they exchange securities nearing redemption with longer-dated ones. This increases future debt burden and leads to an added interest payment load over the years, added the analysts.

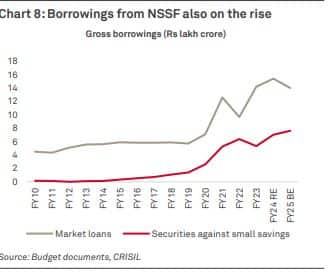

3. Thirdly, the government has been borrowing from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) in large amounts. The government has to pay a higher rate of interest on these compared to market borrowings.

Also read: Explaining government borrowing: A guide to central and state bond markets

Crisil analysts said that the government has done a "stellar job in bringing down the fiscal deficit much faster than expected" and has made fiscal accounts transparent. But, the government needs to continue to improve its tax and non-tax revenues by sustaining high growth in the economy, and needs to run a tight fiscal ship to bring down its debt levels to pre-pandemic levels and the aspirational level of 40 percent, as suggested by the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Committee in 2017, according to the report.