RBI may keep stance unchanged on Thursday but prepare markets for a change

The Reserve Bank of India’s upcoming Thursday policy is expected to be status quoist. Still, there is a good chance it will prepare the markets for a dovish change in October, given the changed global ecosystem.

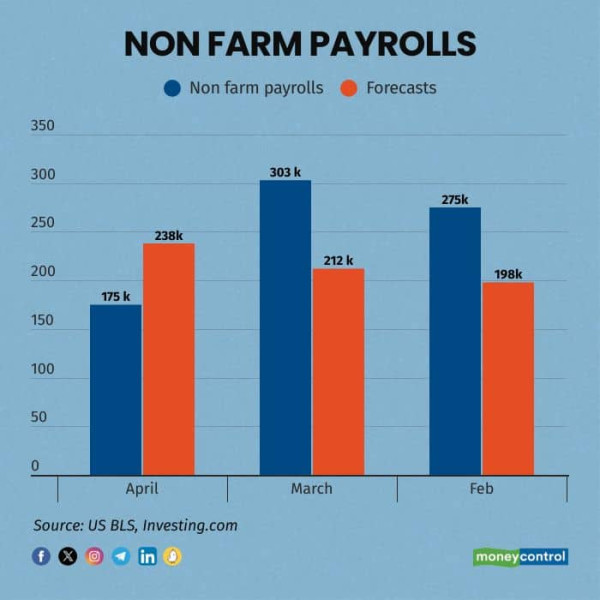

Global macros today are quite different from what they were when RBI announced its June policy. In June the US economy was still surprising with its resilience. Though the Q1 GDP had come in a tad lower than expected, the labour market was still strong. The last 3 payroll numbers were strong and getting stronger:

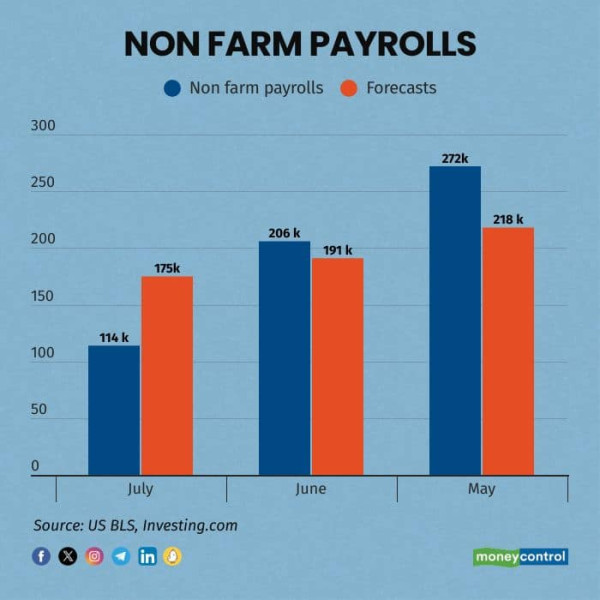

Now, going into the August policy, the last 3 payroll numbers have been falling sharply:

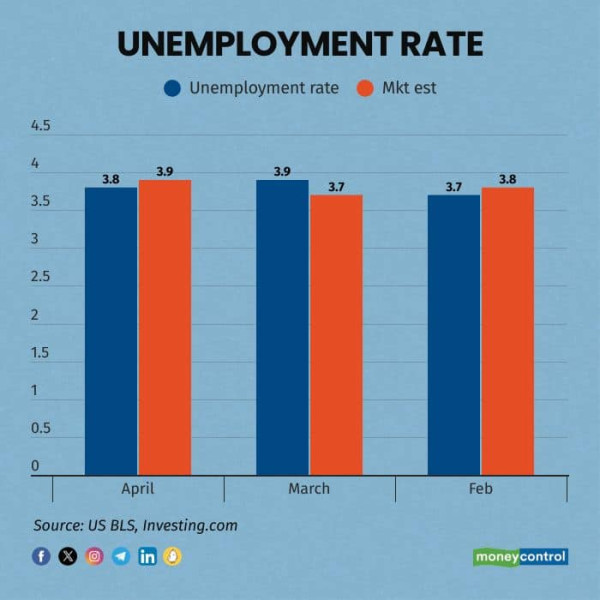

The US unemployment numbers narrate a similar story. Going into the June policy the last three numbers were not rising, and were sometimes lower than market expectations.

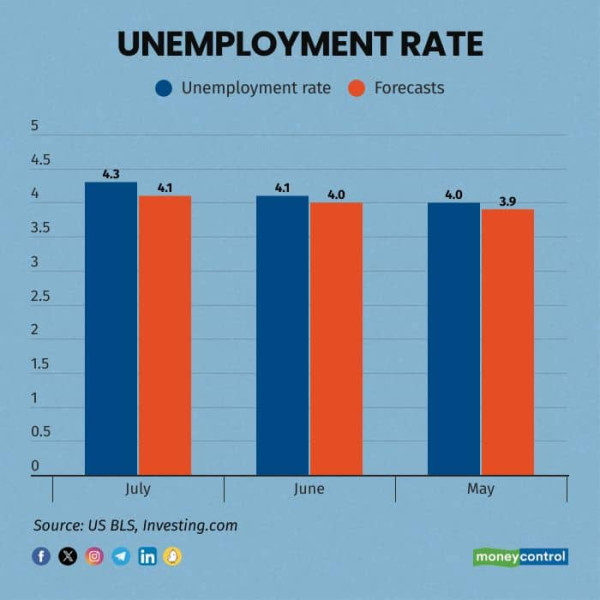

Coming into August, the rates of unemployment are much higher; they are also higher than forecasts.

More importantly, market expectations from the Federal Reserve have changed markedly. Ahead of the June policy, the Fed was expected to cut rates only once in 2024, probably by 25 bps in September. But now fed fund futures indicate that the Fed may cut a minimum of 75 basis points and a maximum of 125 basis points in 2024. The September cut is expected to be a 50 bps cut while a part of the market is expecting even an inter-meeting cut.

Of course, the RBI has repeatedly warned that it is not influenced by what the Fed does and that it sets rates solely based on domestic factors. However, it is tough to see the RBI being entirely uninfluenced by U.S. yields falling from 4.4% during the June policy to 3.8% today.

The state of the US economy becomes important because it is still the largest in the world and until recently has been a resilient engine of global growth. Now that engine seems to be slowing. The recently much quoted Sahm rule forecasts that the U.S. is already in a recession (Sahm rule states that if the 3-month moving average of unemployment rates (which currently works out to 4.15%) is at least 50 bps higher than the lowest unemployment rate in the past year (which was 3.5% in July 2023) then the U.S. economy unfailingly slips into recession.

While the RBI and the MPC rightly won’t worry about the Fed’s rate policy, they have to model a likely slowdown in global growth, if indeed, there is a US recession, especially at a time when the second largest economy, China is already in the grip of a slowdown. Not only has Chinese domestic demand collapsed, the country is also exporting a whole range of products from electric vehicles, to solar panels to steel to garments in the global markets at below-cost prices, going by the number of countries imposing anti-dumping duties on Chinese goods.

While the deflationary impact of Chinese exports was known in June as well, the now emerging slower US growth can have a further deflationary impact. This is starkly visible in crude prices which have tanked to $76 per tonne despite rising tensions in the Middle East, with Iran vowing to join the war against Israel. Experts point out that demand is so weak that crude prices are not able to hold up anymore. In fact, other commodities like copper are already at 4-month lows reflecting weakness in global demand.

The global ambience may not already force the RBI to lower its India growth and inflation forecasts, but indicating a downward bias to its forecasts is a small possibility. Remember, the Economic Survey also forecast India’s GDP in the current year at 6.5% to 7%, a shade lower than the RBI’s forecast of 7.2%.

As for inflation, the RBi can’t be expected to lower its 4.5% forecast for the year just yet, when the heat of rising vegetable prices is even being felt in parliament. The June inflation actually came in higher than expected at 5.08% because of 29% rise in vegetable prices. But the monsoons which were feared to be delayed during the June policy, are now presenting a picture of bounty. The RBI can reasonably hope that food prices will cool soon. Core inflation has anyway been slipping consistently and with slowing global growth, may remain lower for longer. An added comfort to the RBI on inflation comes from the faster-than-expected fall in fiscal deficit.

Respondents to the CNBCTV18 poll were unanimous that there won't be any cut in rates. An overwhelming majority of the polled bankers and economists also said the stance won’t change, but two members of CNBCTV18’s Citizens’ Monetary Policy Committee said the RBI ought to change its stance to neutral.

Already two members of the RBI’s MPC – Dr Varma and Dr Goyal voted in June for a stance change. With the global economy likely to slow, the doves may push home their point more strongly at the MPC meeting currently underway. More importantly, with there being a good chance that the Fed cut rates by 50 basis points in September, it may be strategic for RBI to create some wriggle room for itself, to flag some dovishness at least in the post-policy presser, if not in the statement itself. Dealers will be closely parsing the statement and the press conference for such signs of dovishness.

To RBI’s credit, the central bank has already loosened the inter-bank liquidity situation somewhat. From a deficit in the banking system for a better part of FY24, interbank liquidity has become balanced as reflected in the softer daily call rates.

Lately, the RBI has been more worried about financial stability than inflation. It moved against likely loose lending of unsecured loans as early as November last year when it raised risk weights on unsecured loans. More recently it has been worried about soaring stock valuations and the rising volumes in equity derivatives. While the recent global market rout has cooled valuations somewhat in India, the RBI may still be wary of lowering its cautious tone, lest that gets the markets frothier.

The RBI policy will be watched more closely for what it says on the current war for deposits waged by banks. The ultra-low deposit rates during covid had pushed savers away from banks to invest in stock markets and mutual funds. This cash remains in the banking system but in the form of short-term highly mobile funds. Banks have to maintain liquidity cover for such deposits. Mobility of deposits has increased with the spread of digital payments and the RBI recently released draft rules mandating banks to increase their liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) for short-term unstable deposits. Bankers say, under current LCR rules, already banks are forced to invest 27% of their deposits in high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) ie in government bonds. The new rules will push up the HQLA to 29%. Adding the 4.5% cash reserve ratio, one-third or 33% of all deposits raised by banks will be absorbed by statutory reserve requirements. The recent draft LCR rules, if notified as is, will accentuate the competition for deposits and push up both deposit and lending rates.

Any dovishness on the part of RBI, thus, won't have any impact on bank lending rates. It can at best push down bond yields and push more commercial borrowers to the bond market. The RBI’s statements on the draft LCR rules will be more important to bankers than will be its statements on inflation and interest rates

All told, the Thursday policy will be watched more for the RBI’s talk. Not so much for its walk