Rise of extremism gives Germany’s Leaders another wake-up call

Germany’s centrist leaders must heed the message that voters keep sending them: If they want to avert a descent into extremism, they need to offer a much bolder vision for the country.

The latest wake-up call came from elections in the eastern states of Saxony and Thuringia, the latter of which the far-right Alternative for Germany won outright — a troubling post-war first for a party whose local leader has used banned Nazi slogans in speeches. More telling, though, was the sudden success of the far-left Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance, launched only in January to ride the same wave of popular discontent that has fueled the AfD’s rise. The result suggests that voters are simply fed up with the status quo, not longing for the fascist past.

Their dissatisfaction is understandable. Just a decade ago, Germany was in the European vanguard. Its export-oriented economic model delivered impressive growth. Its efforts to combat climate change led the world. When then-Chancellor Angela Merkel made the monumental (and controversial) decision to welcome almost a million mainly Syrian refugees, her promise that “we’ll manage this” was believable.

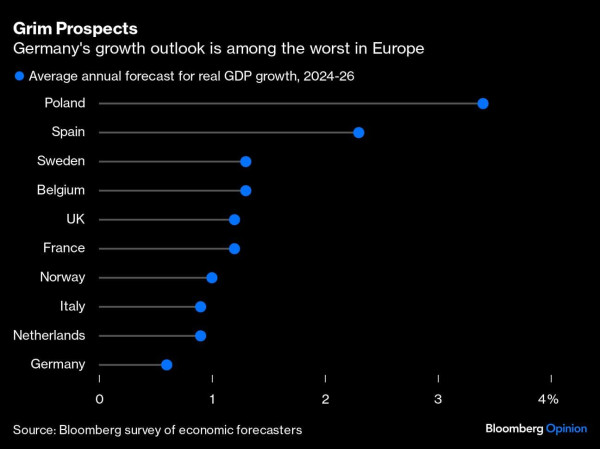

Now the economy is in the doldrums — thanks in part to a war-related energy-price shock and growing competition from China, but also to abundant red tape and a long-running lack of public investment in infrastructure. National champion Volkswagen AG is considering the first German plant closures in its 87-year history. Trains don’t run on time. On the green front, ham-handed efforts to promote everything from heat pumps to ecologically friendly farming have stoked anger among homeowners and farmers alike. Despite progress in integrating refugees, people increasingly see immigration as a problem — a situation worsened by a recent spate of violent crimes allegedly committed by foreigners.

Germany’s mainstream parties need to unite around a plan to break out of the malaise and convince voters that they’re capable of following through. This should include a new economic model focused on investing in productivity, unleashing domestic demand and attracting private capital. It requires bringing a burdensome and unduly paper-based bureaucracy into the 21st century. And it entails making the case for immigrants — desperately needed to bolster an aging labor force — to a skeptical populace.

The current ruling coalition — an uneasy mix of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left Social Democrats, Finance Minister Christian Lindner’s center-right Free Democrats and Economy Minister Robert Habeck’s Greens — hasn’t proven up to the task. Although they’ve laid out plans to revive growth, they can’t even agree on a fiscal policy that would allow for the necessary public investment. Scholz has been making tactical sops to extremists, such as tightening asylum requirements and limiting support for Ukraine.

So far, mainstream parties’ refusal to cooperate with the AfD will probably keep it out of power in Thuringia. The same might happen at the next federal elections, scheduled for September 2025. But such firewalls — or an outright ban of the AfD, as some have proposed — won’t stop the rot. If centrists want to win the country back from the extremists, they’ll have to come up with something more inspiring.

Credit: Bloomberg