US Federal Reserve’s criticism is cheap, and it’s mostly mistaken

I have listened to people bellyache about the Federal Reserve my entire adult life: Alan Greenspan lowered interest rates too much after the dot-com crash in 2000. Ben Bernanke printed too much money to bail out banks during the 2008 financial crisis. Janet Yellen kept rates too low for too long in the mid-2010s. Jerome Powell was too slow to see inflation coming — and now he’s too slow to spot a recession.

Yet over those nearly three decades, the Fed has overseen a historic period of stable prices and low unemployment, interrupted only three times by forces largely outside the central bank’s control — namely, the twin speculative manias involving internet stocks and homes and the Covid pandemic. Each time, the Fed intervened boldly and under a hail of criticism to fend off a deflationary spiral and to shore up the job market.

I shudder to think what would have happened if the Fed hadn’t stepped in to rescue the financial system in 2008 or to keep credit flowing to state and local governments, employers and households in 2020. Those rescues were not perfect, but the Fed deserves at least as much praise as criticism.

With the weight of that long history, Powell addressed skeptical Fed watchers last Friday at the central bank’s annual gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In the chair’s usual diplomatic but not fully intelligible Fed speak, Powell hinted that the central bank would begin lowering interest rates soon, as it focuses less on fighting inflation and more on supporting a weakening job market. He also acknowledged that the Fed is not all knowing, as if it needed saying — a generous gesture nevertheless given the Fed’s success in taming inflation without trampling on the economy, at least so far.

But I wish Powell had gone further and reminded the Fed’s critics of a few things:

No one has a model for reliably forecasting inflation or unemployment – the two sides of the central bank’s dual mandate. The Fed can’t see higher prices or job losses coming any better than anyone else, particularly in the fog of a global pandemic, which also means it can’t get ahead of it. The best it can do is jump into action when necessary and as quickly as possible to bring both back in line with its targets. And that’s what it did.

The difficulty is that real-time inflation and jobs numbers are limited and imperfect, so the Fed must wait on government agencies to compile the data, which come with a lag, delaying its own assessment and response. Even then, the numbers may not be accurate, as last week’s downward revision in payrolls by 818,000 for the 12 months through March shows.

While the timing is far from ideal, it’s better than the Fed making policy decisions based on a guess about where inflation and unemployment are headed. Investors play that game routinely, and they are wrong at least as often as right — and that may be generous.

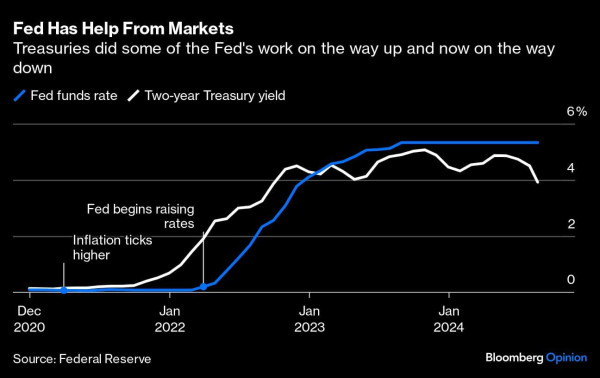

Still, the Fed doesn’t always have to act to have an impact. Markets often respond to macroeconomic developments in anticipation of what the Fed might do, which can have the same effect as the central bank’s actions. For example, the recent bout of inflation began in the spring of 2021, and the Fed didn’t begin raising rates until a year later. But short-term rates didn’t wait around for the Fed. Beginning in the fall of 2021, the two-year Treasury yield rose to 1.9% from near zero before the Fed made a move.

The same thing is happening now. In anticipation of lower rates, the two-year Treasury yield has declined 1 percentage point to 3.9% since May. That’s the equivalent of two 50-basis-point rate cuts without the Fed lifting a finger. It will eventually have to lower its benchmark federal funds rate if it wants the two-year to stay where it is, but the timing is less critical when the market does some of the work.

There also seems to be confusion about the Fed’s job. The Fed is not responsible for the economy. While it attempts to fight inflation without tipping the economy into recession, that may not always be possible. A slower economy is relevant only insofar as it causes unemployment to spike, although it’s possible for the jobless rate to rise but remain below unacceptably high levels. We may be experiencing such a scenario now.

Nor is the Fed responsible for the stock market. Yes, a market bust could move inflation and unemployment in undesirable directions, as it did in the early 2000s, but even the savviest professional investors can’t predict bear markets. And in any event, the last thing investors want is for the Fed to tell them that their stock bets are overcooked. If investors think the Fed will rescue them from a declining stock market absent a material impact on inflation or jobs, they are mistaken.

As things stand, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge — personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy — is down to 2.6% year over year through June and moving toward the central bank’s 2% target. The Treasury market also anticipates that inflation will run at about 2% over the next five years. If the trend continues, the Fed will likely lower the fed funds rate to a range of 0.5% to 1% after inflation from a real rate of closer to 2.5% to 3% now.

Short-term interest rates are nearly there already. With the two-year Treasury yield at 3.9%, the real rate of 1.3% is only modestly higher. That seems reasonable given that inflation has not yet reached the Fed’s target, and that unemployment remains subdued in historical terms. Against that backdrop, it doesn’t seem as if the Fed needs to lower rates urgently.

Don’t get me wrong, I can wrestle with the Fed as well as anyone. I might have given banks less room to load up on derivatives in the years leading up to the financial crisis. I might have lifted rates above zero sooner during the 2010s despite persistently low inflation. But that may be hindsight talking.

More often, I wonder if we’ve become so accustomed to having one of the most sophisticated central banks in the world — and all the benefits that come with it — that we take the US’s relative stability for granted. The Fed has handled the post-pandemic period, and the three decades that preceded it, about as well as can reasonably be expected. It should take the time, if it feels it necessary, to have more confidence that the inflation fight is won.

Credit: Bloomberg